| In Brief |

|

A recent study has highlighted a concerning phenomenon: some hospital bacteria can degrade medical plastics. This finding calls into question the durability of these materials, which are essential to modern medicine. Researchers at Brunel University London found that Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a bacterium often associated with antibiotic-resistant infections, can metabolize polycaprolactone (PCL), a plastic commonly used in dressings and medical devices. This discovery raises questions about patient safety and the integrity of care in hospitals.

Plastic as Fuel for Pathogens

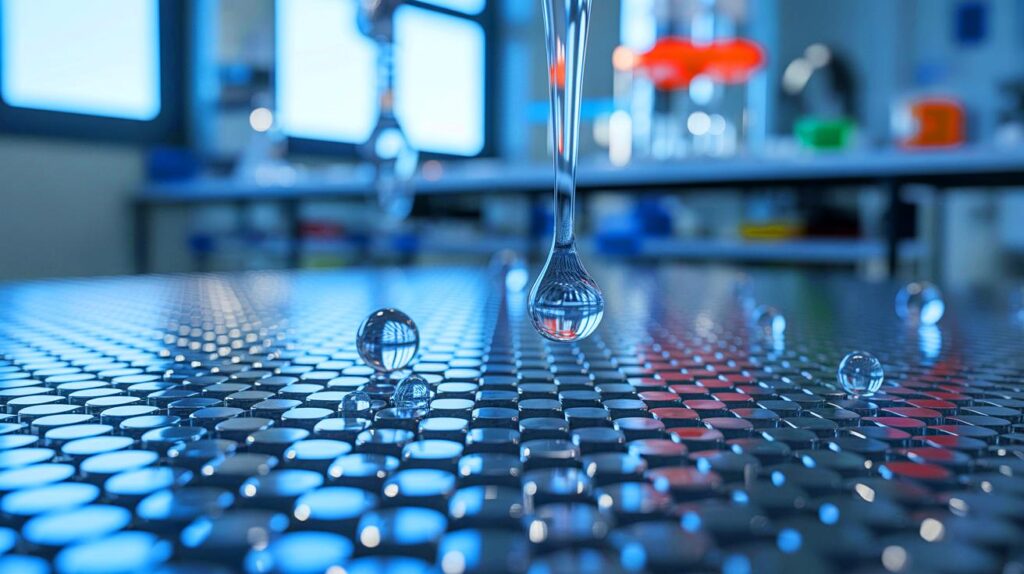

Researchers isolated an enzyme named Pap1 from a strain of Pseudomonas aeruginosa taken from an infected wound. In laboratory tests, Pap1 proved capable of degrading about seventy percent of a PCL sample in one week. The alarming aspect is not just the breakdown of the material but the fact that the bacterium uses this plastic as its sole carbon source.

The degradation of these plastics is directly linked to the formation of biofilms, which are multicellular aggregates of bacteria adhering to surfaces. These biofilms complicate infection management and increase the risk of serious consequences, especially for patients with implanted medical devices. The bacteria’s ability to consume plastic could contribute to their persistence in hospitals and promote nosocomial outbreaks. This highlights the need to develop more resilient plastics and monitor pathogens for such enzymes.

Broader Implications

While the study focuses on PCL, it is likely just the tip of the iceberg. Genomic analyses suggest that other pathogens may also possess enzymes capable of attacking medical-grade plastics. This poses issues for many commonly used materials, such as polyethylene terephthalate and polyurethane, which are crucial in catheters, dental implants, and surgical dressings.

The discovery that these organisms can degrade plastic not only explains their persistence in hospitals but also may clarify why some outbreaks are particularly stubborn. Plastic is ubiquitous in modern medicine, and some pathogens seem to have adapted to decompose it, underscoring the necessity to understand the impact of this phenomenon on patient safety.

Repercussions for Hospital Management

The findings of this research force a reevaluation of how hospitals manage infection risks. The bacteria’s ability to degrade plastics could mean they persist longer on hospital surfaces, thus increasing the risks of nosocomial infections. Hospitals may need to reconsider their use of certain materials, favoring those less likely to be degraded by these bacterial enzymes.

The formation of antibiotic-resistant biofilms complicates the situation even further. Infection management may require new approaches, potentially including more aggressive treatments or alternative materials. This discovery calls for heightened vigilance in disinfection and sterilization protocols, as well as ongoing research into developing more durable materials.

Toward an Uncertain Future

This study raises numerous questions about the future of medical materials and their interaction with microbes. The implications of these findings are vast and could transform our approach to hospital safety and the development of medical devices. As researchers continue to explore this field, how will healthcare systems adapt to these new bacterial threats?

This combines the various elements from the provided content and adjusts titles to capitalize only the first word for consistency.